Does the world need another review of the Devonshire, described by Esquire as “the buzziest pub in the world”? Quite possibly not, because since opening at the start of November 2023 everybody has been there, it seems, and it’s arguably all been said.

Most of the U.K.’s national restaurant critics have been – your Dents, Corens and Parker Bowleses – and so have a plethora of restaurant bloggers, from the good to the bad to the bad and ugly (some even paid). The Topjaw crew are regulars, and boss level grifter Toby “Eating With Tod” Inskip is too: he even took poor trusting Phil Rosenthal there when he visited the capital. Phil clearly hadn’t been warned by his researchers that he was sharing a platform with U.K. hospitality’s biggest Farage fan (yes, even more than William Sitwell).

The brainchild of celebrity pub landlord Oisin Rogers, Flat Iron founder Charlie Carroll and Fat Duck alumnus Ashley Palmer-Watts, the Devonshire is a place you might well know about even if all of London’s many other hyped openings have passed you by. Nowhere, I suspect, has cut through to the national consciousness outside the London hospitality bubble as effectively for as long as I can remember.

Its ascendancy has tied in with a renaissance in the popularity of Guinness – some people claim that it’s the best Guinness in London, although they also said that about the Guinea Grill, Rogers’ previous pub – and the birth of a class of drinkers that think loving Guinness is an acceptable substitute for having a personality.

It’s a game of two halves, the Devonshire. The diners eat upstairs on a menu of British pub classics, the drinkers congregate downstairs where the Guinnesses line up on the bar, all guaranteed to find a home. Reservations are almost impossible to snag – unless you’re famous, in which case space will always be found for you, possibly in the pleb-free private space behind the velvet rope. Turn up on the right night (by which I very much mean the wrong night) and Ed Sheeran might be contributing to an impromptu ceilidh: let’s hope for everybody’s sake that he doesn’t play Galway Girl.

Awards have followed on from all those critical plaudits. In its first full year the Devonshire was listed as the second best gastropub in the U.K. (that same year the Guinea Grill, previously in the top 100, vanished without trace). At the beginning of 2026, SquareMeal named it London’s 42nd best restaurant. The National Restaurant Awards, meanwhile, placed it as the 12th best restaurant in the country last summer. So people rate the food: Michelin’s new Bib Gourmands were announced at the start of February and the Devonshire wasn’t among them, but you could easily make a case that it’s one of the very few restaurants in London that doesn’t need any help from the tyre man to put bums on seats.

You could easily think that the approbation is universal, but it isn’t. One of the London food subreddits I frequent had a discussion about the Devonshire a few months ago, and I heard quite a lot of criticism. Style over substance, more than one person said. Glad someone else agrees – utterly forgettable food, said another. In all honestly I came away massively disappointed by pretty much everything else for the money spent and the hype said one person, adding that he would have been better off going to Hawksmoor. It’s just okay was another pithy summary.

The comment that stuck with me was this one: Not been myself but I’ve not known anyone come back saying it was worth the hype. Because I was trying to pick through and differentiate between people who had been and not been impressed and those who simply took against it because of the hype, the exclusivity, the difficulty involved in getting a table and the inherent contradiction behind pretending to be egalitarian and always finding space for the famous and influential. Now, I have sympathy with all those viewpoints, but what I wanted to know was whether the food and the experience justified jumping through all those hoops.

Anyway, you get a review of the Devonshire this week for two reasons. One is that last month the Devonshire was named as the best gastropub in the whole of the U.K., nicking the top spot after coming straight in at number two the previous year. The other is that, idly looking at their exceptionally user-unfriendly booking page I managed to find a table free for lunch at a not unreasonably late time and thought that this was a now or never opportunity. Time to chip in, seemingly after everybody else has had their say, to try to sift fact from hype.

The pub and the restaurant are fairly separate entities, so you go in through the ground floor, past the mass of Guinness drinkers, to the welcome desk at the end where they lead you up the stairs, past framed pictures of Kate Moss, Nigella, Marianne Faithfull, and into the set of dining rooms on the first floor. The pub itself does a good job of looking like it has been there forever, but it is a manufactured image: it might well say SOHO SINCE 1793 on the front but before they turned it back into a pub it was various things, including a restaurant owned by attempted comeback king Jamie Oliver.

The room I was in (the Chop Room, according to my bill) was a very pleasant, airy one with plenty of light coming in from the big windows, a Gilbert & George taking pride of place on the white brick wall. The clientele, as far as I could tell, was a real mix containing what looked to me like a fair proportion of gastronomic tourists: that’s no criticism, as I was one myself. I wondered how many of these people were regulars, and how many were drawn in by the buzz.

What can’t be denied, though, is that the Devonshire has made the decision to absolutely cram tables into those rooms. I was put at a table for two, in the middle of a row with a table on either side, the gap between them one even Kate Moss couldn’t have made it through. I asked if I could move to an end table, so at least one of my arms could move unobstructed and, after what felt like a lot of deliberation, it was decided that I could.

The last time I was in a dining room this cramped was undoubtedly in Paris, the kind of places where you need to ask your neighbours to leave their seats if you wanted to go to the loo. In fact, I’ve only ever had those experiences in Paris, before the Devonshire. I guess the benefit of the doubt would say that they want to accommodate as many of their clamouring prospective diners as possible.

Much has been made of the Devonshire’s no choice set lunch menu – prawn cocktail, skirt steak, chips and béarnaise sauce, sticky toffee pudding – which is indeed decent value at £29. But I didn’t come all that way to eat the set menu, and on the à la carte there is almost a second, slightly more expensive set menu hiding in there, consisting of the dishes everyone orders: the scallops, the beef cheek suet pudding and the chocolate mousse.

That’s a decent way to experience the menu which is still pretty affordable, although unless you’re ordering a gigantic t-bone steak or the wagyu ribeye prices aren’t stratospheric: most mains max out at £40 and only a couple of starters will set you back more than £15. I made my order, asked for a glass of biodynamic Alsatian riesling from the very attractive list of wines by the glass and sat back, looking forward to a long, leisurely Soho lunch. That didn’t happen, as we shall see.

I’m going to talk about all the food first and get it out of the way, because a lot of it was rather good and yet it didn’t stop it being a deeply disappointing experience. We’ll get to that. First off, the Devonshire will bring you lovely, salt-speckled soft little buns, dished up from a hot tray with tongs, as many times as you like, along with room-temperature butter. I held fire on eating mine, because I thought the bread would be useful with my starter, but when I asked one of the sparkling, friendly servers she told me there was no need to show such restraint.

I wanted the bread for my starter, the starter nearly everyone orders. Three fat scallops, lavished with batons of bacon, topped with crumb and bathed in a sauce bright with vinegar, were pretty much everything people said they would be. The scallops, grilled in the shell, were just the right texture, the firm side of jelly, and a joy to slice, dip, dab and devour. But everything else perfected the synthesis: a really extraordinary mixture of salt and vinegar, of soft and crunchy, a dish you could eat over and over again. Which, given that you got three of the blighters – not bad for £18 – is pretty much what you got to do.

I cleaned each of those shells with a judiciously torn piece of bread, and I thought that, in this case at least, the hype was simply an accurate description. Next time I go to the Nag’s Head and order a packet of Scampi Fries and Bacon Fries I will sandwich one of the former between two of the latter, eat it, close my eyes and remember that combination of flavours elevated to an iconic level.

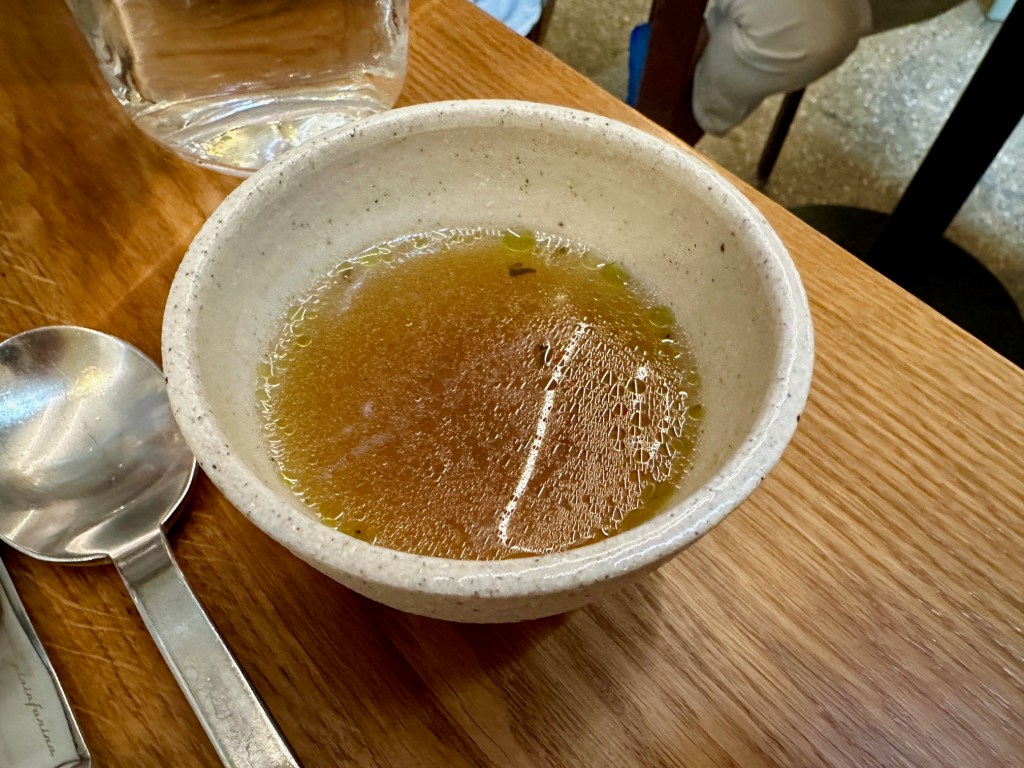

I also tried the potted shrimp, which I liked an awful lot: a deceptively big portion of these with a comforting hug of nutmeg and a lid of soft, spreadable butter. It didn’t look like much at £14 but that pot was as packed with prawns as the room was with tables – well, almost. It made the three mingey pieces of stripe-tanned crustless Melba toast look a little inadequate: I would have liked more, and resorted to eating the last of the prawns with a fork. Still, there was a constant procession of more bread, so you couldn’t very well complain.

So far so good, but my main course – the ox cheek and Guinness steamed pudding – struck a bum note. It arrived with some ceremony, anointed with gravy at the table (“I always love doing this bit” said my server), and it looked: well, it looked about as attractive as this dish, a symphony of beiges and browns, can look. But it was when you cut into it that it started to disappoint.

Its walls were claggy and thick – now, I know that’s the nature of this particular beast, but the filling is meant to justify that. And here it just didn’t. The amorphous brown mass obviously had bone marrow in it, which gave it that intense, savoury, mouth-coating note. But the bits of beef cheek were small and not cooked enough to truly fall apart, so the whole thing felt like a stodgy trudge.

Dipping the admittedly very good duck fat chips into that slightly bland gravy wasn’t transformational: in fact, the chips were better on their own. And my firm, nutty peas with ribbons of white onion and more of those batons of bacon were pleasant enough but unexceptional: if it had had some cream in it, proper à la Française stuff, I would have liked it better. Perhaps I should have gone for the carrots, or the creamed leeks, but by this point – I’ll explain shortly – I was starting to feel apathetic about the road less travelled.

I had dessert, too, I should add. The Devonshire’s chocolate mousse is a very agreeable example of the genre, not the best I’ve had but not a million miles away from it. It came with a jug of cream, which I wasn’t sure it needed, and three beautifully boozy cherries. It needed more of those.

Throughout my meal I think one of the things I liked best about the Devonshire was the people watching. Despite it being the closest thing London has right now to the original Ivy, before it turned sour, I didn’t see any celebrities. Rather it was like being in Soho House, seeing people who thought their very presence there made them almost famous. A few tables along from me a table of tourists enjoyed their coffee and, it appeared, took some leftovers away in a cardboard box: good for them.

Directly opposite me were two men in gilets and quarter-zip jumpers, both practising exactly the same techniques of male pattern baldness concealment, who looked as if they’d come out of the same vat in quick succession. They were pally with the servers in a way I don’t think I’ve ever attempted and ordered the biggest piece of meat they could find on the menu, the way people who identify as alpha males do.

But my favourites were the two lovely gents who sat on my left, who had discovered the Devonshire on YouTube of all places and were very excited to be there. Gent A sipped his Guinness and said to Gent B “if that was your last beer you’d die a happy man”, shortly after saying “this is the highlight of my whole week”. They ordered the same things as me, but were slightly behind me so they got a preview of the scallops and the suet pudding because, as I said, there’s almost another set menu within that à la carte.

Not only had they done their research – read all the reviews, read all the articles and puff pieces – but they engaged in some strangely endearing willy waving about it all. “Do you know how many scallops they get through a week?” said Gent A. Gent B didn’t know, so Gent A told him. “I wonder where they come from?” said Gent B. “It’s Devon or Cornwall I think” said Gent A (I knew this one – it’s Devon – but I didn’t interject). Then Gent B asked if Gent A knew how many pints of Guinness the pub got through in a week, and the game of Top Trumps began again. If I’d known I’d be sitting next to them I wouldn’t have needed to research this review at all. I could have just surreptitiously recorded their conversation.

“That bacon, mate” said Gent A about his scallop dish. “It’s Iberico bacon, it’s aged for 5 years.”

I kept my counsel: maybe you can indeed age bacon for 5 years, but it sounded unlikely. But I got a picture from this of the kind of person the Devonshire might appeal to and how it has permeated beyond the London food scene, all the blogs praising Cocochine or Row On 5 or prognosticating about who’s going to get a Michelin star next. The Devonshire appeals to TikTokers, and people who get their food coverage from YouTube, and it’s as much for box-tickers, in its way, as some restaurants are for star chasers.

So all that said, I need to talk about why the Devonshire was so poor. This bit is always boring and forensic, and makes me thankful for the time stamps on iPhone pictures but here goes. I’ll try to be quick: God knows, the Devonshire did.

I arrived around 2pm, I ordered around five minutes past. Those scallops? They arrived literally five minutes later. Either, like the Guinness on the bar downstairs, they were sitting around waiting for a table to go to or they were cooked and rushed out to me pronto. Either way, that’s not what I wanted at all. Remember that extra dish of potted prawns? That wasn’t part of the plan: I was worried about the breakneck pace, so as I was finishing my scallops I flagged down a server. Could I have an extra dish between my starter and my main please, I asked? I’m really in no hurry, I told her.

The potted shrimp arrived less than five minutes after that conversation and I tried to eat them slowly, in the hope of putting the brakes on. My main course arrived no more than three minutes after I’d finished eating the potted shrimp. And I suppose I could have said something again at that point, but what good would it have done? Would I have said “I’m sorry, but can you take this away and make me a fresh one in about twenty minutes?”

Maybe some diners would do that. But it felt entitled to me, so I ate my main and took my punishment. All in all, from ordering my lunch to my main course arriving was twenty-five minutes at most. And as lovely as the servers were, that says to me that they’ve forgotten something very basic about what restaurants are about. The clue is in the word, hospitality. I read a florid think piece recently about the delights of the solo lunch, a subject I’ve also written about before, but there are no delights in feeling like you’re on a conveyor belt from start to finish. I’d have understood it better, perhaps, if I’d been on the set menu. But I wasn’t.

Those tables that are so in demand at the Devonshire are booked in 2 hour slots, but despite my best efforts to delay things just over an hour had elapsed from taking my seat to getting my bill. In that time I managed to spend £117, including an optional 12.5% service charge which, in the words of the menu, “goes to our amazing staff”. Were they amazing? Well, they were and they weren’t: I have felt less processed in many, many chain restaurants. Perhaps hospitality operates close to its best by being a well oiled machine, but it fails when it feels like a machine.

In some ways that’s what confused me the most: what was the point? Why spend all that money on doing the place up, the Gilbert & George, the hype, the geeking out about the provenance of the ingredients if you’re going to make diners feel like they’re in a bloody canteen? I get that as a solo diner it might have been easy for the kitchen to do my food earlier, less complex than coordinating logistics with multiple dishes at larger tables, but you’d expect any restaurant to manage flow better. Nothing about me, as a solo diner at 2pm, screamed let’s get this over with.

And that’s the sad thing – if I’d loved the food, which was mostly quite nice at best, maybe I too would be going on about where all the meat comes from, raving about the on-site butchery in the basement, regurgitating the many, many facts Gent A and Gent B threw at each other. Instead, the thing I took away from my meal at the Devonshire was that I felt managed and turned, a product rather than the customer. Maybe that’s how they churn so many tables, create that buzz, make all that money. Maybe that’s what they want, and they can be packed until the end of days delivering this kind of experience. But I wonder who, if they had a meal like mine, would go back.

Perhaps they weren’t always like this, and drift and complacency is now setting in. Who cares? You can only make one first impression in London: there are many more fish in the sea, and countless other restaurants there. As I left to scuttle to the Tube in the rain I spotted Brasserie Zedel and Kricket and ruefully thought that my money would have been better spent in either. I probably would have been there longer, and found it much easier to get a table in the first place.

For that matter, a five minute walk away you have the French House. When I think about my lunch at the French House last year, it was everything the Devonshire wasn’t; I had four courses in a restaurant above a pub that is a genuine institution, not an ersatz, invented one. I was there for two and a half happy hours, enjoying the legendary long lazy Soho lunch all the early reviews of the Devonshire claimed that it delivered. I had better food, at a better table, I had far more booze and I spent slightly less money. I’d go there again in a heartbeat, but I won’t trouble the Devonshire’s labyrinthine booking system again.

The best gastropub in the U.K.? Sorry, but no: it’s not even the best gastropub in London. Actually, scratch that. It’s not even the best gastropub in Soho.

The Devonshire – 7.0

17 Denman Street, London, W1D 7HW

https://www.devonshiresoho.co.uk

Since January 2025, Edible Reading is partly supported by subscribers – click here if you want to read more about that, or click below to subscribe. By doing so you enable me to carry on doing what I do, and you also get access to subscriber only content. Whether you’re a subscriber or not, thanks for reading.