Every year, without fail, a handful of new U.K. restaurants get hyped beyond measure. Every critic goes there, usually within the space of a fortnight, and every critic raves in their own hyperbolic way. Those places become impossible to book, if booking them were ever possible in the first place, and move into the heart of smugness: proper “if you know, you know” territory. These London restaurants – it’s always London, of course – are invariably hailed as evidence that it’s the most exciting food city in the entire world, mainly by restaurant reviewers living in London and writing for the national papers (or, perhaps more understandably, the Evening Standard).

So last year, it was all about Mountain in Soho and Tomos Parry’s cooking over fire (“can a dish be too good for itself?” wibbled Tim Hayward in the FT). Or Bouchon Racine, Henry Harris’ bistro. Jay Rayner described himself as a “huge dribbling admirer”, presumably to put people off booking a table, or for that matter ever eating again. And of course, there was Kolae, but you already know whether that’s good, don’t you?

And this year? Everyone has lost their collective marbles over Josephine Bouchon, Claude Bosi’s earthy Lyonnais restaurant on the Fulham Road, and Giles Coren, Tom Parker Bowles and Jay Rayner all went to the Hero in Maida Vale seemingly in the same fortnight. Giles Coren dined with Camilla Long, which means that for once he might have had an even worse time than his dining companion. I have a friend who everybody loves, who never has a bad word to say about anybody: you should hear his vitriol on the subject of Camilla Long.

Of course, the hype beast to end all hype beasts, this year, has been the Devonshire, the Soho pub run by the chap behind Flat Iron and Oisin Rogers, the closest thing the U.K. has to a celebrity pub landlord who isn’t Al Murray. Nearly all of the U.K.’s broadsheet restaurant reviewers descended on the Devonshire, mystifyingly all being able to land a table despite it being nigh-on impossible to do so, unless you’re famous. It’s almost as if there’s one rule for civilians and one rule for everyone else. Almost.

Coren even went all meta, writing in his review about being desperate to file his copy first despite seeing Tom Parker Bowles and Charlotte Ivers in there literally at the same time as him (Grace Dent, always at the cutting edge, finally got round to it last month). Still, nobody was going to match Coren for overstatement: “It’s just insane, what they’re doing” he gushed, about a pub taking the unprecedented steps of serving beer and cooking food.

It would be temping to review The Devonshire, if I could ever get a table. I used to know Rogers, a little, over a decade ago, and even got drunk with him a couple of times; he’s enormous fun, and a very canny operator. You have to take your hat off to someone who has always managed to keep in with whoever is making the weather in the notoriously bitchy world of London food, and Osh has managed simultaneously to be on good terms with everybody from Fay Maschler to the restaurant bloggers of the late Noughties and early Tens, all the way through to those tacky toffs from Topjaw. He’s always known exactly who to have onside, and is possibly even better at doing that than he is at running a pub.

But actually, I’d be more likely to go to his previous place, the Guinea Grill, which everybody thought did the best Guinness in London before Rogers jumped ship, and which also does the kind of steaks, puddings and pies people associate with the likes of Rules. All that without having to bump into the likes of Ed Sheeran? Count me in. And it’s interesting to me, that: you have places like Rules, or St John, that have been there for ever, and you have places like the Devonshire that are the new upstarts. Between those two types of restaurant? Sometimes it feels like there’s nothing at all.

But how can restaurants ever go from being the hot new thing to becoming institutions when everybody’s attention spans have been destroyed by social media, influencers and restaurant critics desperately craving the new? And what becomes of the flavour of the month when things settle down and the bandwagon rolls on to the next place, and the place after that? That’s why this week, after meeting Zoë from work up in the big smoke, catching the Elizabeth Line to Farringdon with what felt like a thousand West Ham fans and gulping down a handful of Belgian beers at the beautiful Dovetail pub, we mooched across to Brutto for our evening reservation there.

Brutto, you see, was one of The Restaurants Of 2021. Critics flocked to it that year, not necessarily because a trattoria modelled on the restaurants of Florence was what the capital was crying out for, but because this was the comeback restaurant of restaurateur Russell Norman. Norman’s Polpo group of restaurants, fifteen years ago – no reservations, small plates, typewritten menus on brown paper, Duralex glasses – probably did as much as any other to change the way people ate in London. It’s just insane what they did, as Giles Coren might have ineptly said.

I went to Polpo a little just after it opened, and offshoot Polpetto after that, and they were brilliant places to eat, although they never entirely overcame that feeling, when the bill arrived, that you’d spent too much on too little. But then came the unwise expansion, including branches in Bristol and Brighton, and then came the crash: Norman made his exit in 2020, and now only two branches remain.

And then, pretty much a year ago, Norman died suddenly and was mourned by seemingly everybody in the food world. Yet even if you never ate at one of his places, the likelihood is that in the last fifteen years you have eaten at least somewhere that has done something differently because of one of Norman’s restaurants from all that time ago, and that in itself is an interesting and far-reaching legacy.

Reading all that back it sounds like a bit of a downer, but I find it hard to imagine anybody walking into Brutto would feel down for long. I can think of few dining rooms that make you feel happier to be in them – it was simultaneously snug and buzzy, with tables full of people thoroughly enjoying their Saturday nights and others sitting up at the bar, making the most of Brutto’s fabled £5 negronis.

The dining room is kind of split level, and I guess the room at the front would be the one you’d ideally want to be sitting in, with its banquette and framed pictures arranged haphazardly on the teal wall behind (“it’s like Alto Lounge, but not shit” was Zoë’s take). But we were closer to the bar at a surprisingly good table next to a pillar, and although there was a distinct hubbub, and an effortlessly cool soundtrack seemingly pitched at Gen X duffers like me, it was never uncomfortably loud.

It really was a marvellous place, from the gingham tablecloths to the napkin lightshades to the candles stuffed into wicker-chianti bottles, and I loved it. It had that feeling of otherness I adore, the restaurant as a cocoon, where for the next couple of hours you could kid yourself that you’d walk out of the door at the end of your meal and be somewhere completely different.

It was, however, and I might as well get this out of the way now, dark. It started out as atmospheric, but as the evening went on it started to reach Dans Le Noir levels of stygian gloom. A lovely spot to be in, to drink and talk, but the practicalities of doing some of the things you ideally want to do in a restaurant, like read your menu or see what you were eating, were severely curtailed.

A solitary votive candle in the middle of our table wasn’t really going to help with that, even if the staff – who were on it throughout – replaced it very efficiently when it sputtered and went out. I got told off for getting the torch out on my phone to try and read the menu. Zoë told me that I was ruining the atmosphere for everybody, and I’ve since discovered that this is allegedly a boomer thing to do, for which I can only apologise.

Once Zoë had taken some pictures with her phone, in night mode, naturally, and AirDropped them over to me, I managed to get a decent look at the menu, which was of course typewritten. It was everything you’d want it to be, mostly: compact, affordable and interesting. Starters were mostly under a tenner, pasta dishes were closer to twenty and so were the secondi, with the exception of Florentine steak which is sold by weight. I think in the past I’ve seen these listed up on a blackboard, so as to say that when they’re gone they’re gone. Maybe they’d already gone, because our server didn’t mention them to us.

The thing you don’t notice on the menu, at first, is that there’s no fish to be seen anywhere. I saw it written on a mirror in the dining room that Brutto doesn’t serve fish, and although it’s often not my first choice it was still odd to see it completely excluded. It gave the dishes on offer a certain brownish hue, or that could have been the dim lighting, but I suppose it worked on a nippy evening with London well on its way to winter. And it’s not as if I minded, much. The negroni was fierce and medicinal and, lest we forget, only a fiver and, on top of those Belgian beers from earlier on, positively knocked the edges off the day.

I don’t sense that Brutto’s menu has changed enormously since it was first reviewed three years ago, because many of the dishes on offer were talked about in those initial reviews. One definitely was – coccoli, which translates as “cuddles”, and is little fried bits of dough with prosciutto and a small pot of tangy stracchino cheese. Remember when I said that these restaurants attract bucketloads of hype? Jimi Famurewa, then of the Standard said that they were “one of the year’s best dishes”.

I don’t know about that, but they were rather enjoyable. More doughnut than doughball, and pleasant enough with little slivers of ham and a small dollop of the cheese; there wasn’t enough stracchino, but I imagine there never is. But the problem with hype, however old it is, is that it almost sets you up against something. I bet the people who raved about these would have sneered at good old Pizza Express. It reminded me of a restaurant in Shoreditch I used to love called Amici Miei which did a similar dish to this, but far better and completely unsung. But then it hadn’t been opened by Russell Norman, that was the problem.

The other starter was three things that in isolation are hard to beat. Very fine, extremely salty anchovies, with decent salted butter and sourdough from St John just down the road. It’s impossible to argue with this really, even if it involves no cooking, and all three things were good. Zoë adored it, I wasn’t convinced it was really any more than the sum of its parts. In fairness though, this dish was just over a tenner and even in Andalusia seven anchovies of this quality might well set you back more than that.

By this point we were on the red wine, The wine list is all Italian, with lots to enjoy, provided you can read the bastard thing. Bottles start at thirty-six pounds and ascend quickly into three figures from there, and we settled for a Montepulciano closer to the shallow end for sixty-two pounds. which retails for eighteen quid online. Was it worth sixty-two pounds? We’ve established over eleven years that I don’t know a lot about wine, but I’d say maybe not.

For me the pasta dishes were probably Brutto’s greatest strength, and easily the thing I most enjoyed. I’d been tempted by pappardelle with rabbit, but in the end the classic tagliatelle with ragu was too hard to resist. And it was as close to perfect as this dish gets in this country, fantastic al dente ribbons of pasta and a rich, sticky ragu that hugged its curves closely. I’ve always been somewhat sniffy about this widely-held belief that there should be more pasta than sauce, but eating this, for once, I got the point. Everything felt like it was completely in order, in absolutely the right proportions.

Because Brutto is a homage to the trattoria of Italy, they left a bowl of grated Parmesan at your table, with a spoon. But because we were still in London, there wasn’t a lot of Parmesan in it.

For me if anything, Zoë chose even better. Her gramigna, a little spiral shape from Emilia-Romagna, came – as it does in that region – tumbled with sausage and friarelli and was a real joy. But don’t be fooled by the brightness of these pictures from Zoë’s iPhone: by this point it was getting more and more difficult to see what was going on. Even so, these two dishes, to me, highlighted that when it came to pasta dishes restaurants like Brutto or Bancone are still light years ahead of well-intentioned pretenders like Little Hollows in Bristol or bandwagon jumpers like Maidenhead’s Sauce And Flour.

I complained recently that Reading was still lacking a really good Italian restaurant and someone popped up and said “what about Vesuvio?”. And I said that I was looking for somewhere more genuinely Italian and less like a better reimagining of Prezzo, with more interesting secondi. But actually, I got that wrong: what’s really missing is brilliant pasta like this. Pepe Sale had that, back in the day. So did San Sicario. But since then, this kind of carb-centric comfort has been missing from Reading, and it’s a poorer place for it.

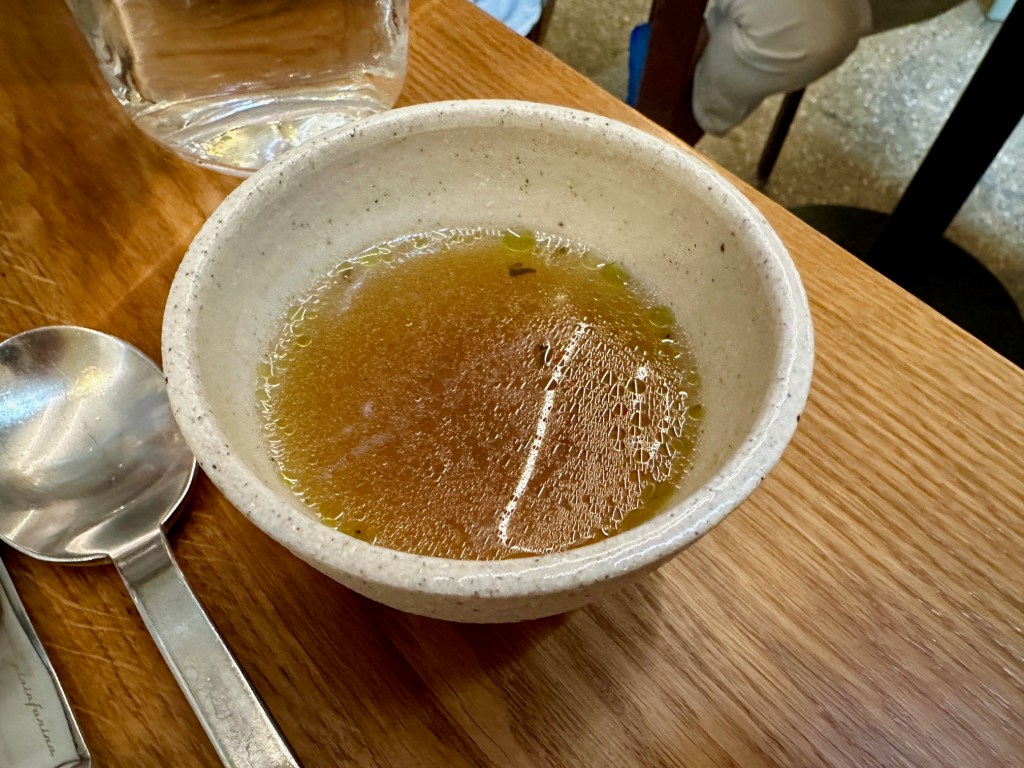

Speaking of secondi, to eat that course at Brutto it does help if you like beef. Three of the options are beef-driven (possibly four, depending on what’s in the bollito misto) and the roasted squash, virtuous though it doubtless was, just didn’t appeal. I had chosen the peposo, a slow-cooked stew of beef shin in a sticky, reduced sauce shot through with whole black peppercorns. And I liked it – it sort of reminded me of a stifado, although with no reliance on tomato or those maverick shallots that make the Greek dish such a delight.

But you know how you feel when you see a picture of a moment you don’t fully remember and you’re not sure if the photograph itself is inventing a memory you didn’t really have? Usually that experience dates back to childhood, but I have it when I look at the picture Zoë took of my main course. I know this is what I ate, the photo has my hand in it and the date stamp to prove it. But for me it was just a pool of blackness. You never quite knew what you were eating, or whether this would be your last big chunk of beef. I’ve always understood the saying that you eat with your eyes, but maybe not as well as I did after having this dish at Brutto. And however convivial the atmosphere was, this is where it took something away for me.

I didn’t need a great view of the roast potatoes I’d ordered on the side to know that they weren’t the best roast potatoes. Decent enough, but lacking that contrast of crunch and fluff that would have come if they’d been parboiled, and scuffed up, and cooked properly in really hot fat. Without that, they were just ballast.

Zoë infinitely preferred her main, which was a variation on the same theme. The same roast potatoes, which she viewed more kindly than I had. A slab of pink roast beef, the fat on the outside mellow and puckered, sitting in a little pool of jus. It needed the peas with pancetta that she ordered with it – I’d have liked these à la Française, with a little cream, although I know that’s missing the point in a Florentine trattoria. Anyway Zoë loved it, although she did admit that it was a tad dry. But if there’s anything our marriage proves – six months and counting – it’s that she has far lower standards than I do.

We had a fair bit of wine left, so we drank that and chatted about all sorts before making any decisions about desserts. Now Zoë works in London she is there every Saturday, and usually knocks off at eight o’clock, so by the time our evening begins, most weeks, it’s time for bed. A rare date night in the capital was a precious thing, and so neither of us was in a rush to bring it to an end. But desserts also meant digestivi, and that meant a Frangelico for her and an Amaro del Capo for me. It’s one of my favourite amaros, with something like 29 botanicals, though the one that leaps to the surface for me is mint.

I could have nursed that for some time, and maybe even had another, but the dessert menu only had a few things on it (putting pear and almond cake on there twice, once with ice cream and once without isn’t fooling anybody). Anyway, one of the items on the dessert menu was tiramisu, which meant that we were both contractually obligated to have one. Is it the dessert I order most often when I’m on duty? It definitely feels that way, and Brutto’s is up there with the best I’ve had – miles better than Little Hollows’, better than Sonny Stores‘, better than anything I’ve had in Reading, even including the wonder of Sarv’s Slice or the sadly departed Buon Appetito.

It properly contained multitudes, managing to be substantial yet airy, innocent yet boozy, simultaneously just the right size and nowhere near big enough. I loved it, and it reminded me that on the many occasions that I skip dessert when eating on duty I’m leaving the play before the final act, taking the book back to the library with the last fifty pages untouched. Brutto understands that a good meal has a beginning, a middle and an end, and that tiramisu was a more than worthy way to bring the curtain down.

With all that done, it was time to settle up and pray that the Elizabeth Line could get us back to Paddington before we were forced to catch one of those final trains back to the ‘Ding, the ones everybody refers to as the Burger King Express.

Our meal – a couple of negronis each, that bottle of wine, four courses each and a pair of digestivi – came to just over two hundred and fifty pounds, including an optional 12.5% tip. I know that’s a fair amount of money, but we had plenty of food and didn’t stint on the wine. Personally, I think Brutto is keen value, although probably more so in its starters and pasta than in its mains or wine list. I could have spent less and enjoyed myself just as much, and if I went again I imagine I would.

But would I go again? That’s the question, isn’t it. And it prompts the time-honoured answer, which goes like this. London is so blessed with restaurants – there are easily a handful of other great places to eat less than a ten minute walk from Brutto – that places have to be truly amazing to keep you visiting time and again. That drives quality, I’m sure, and it makes restaurants work hard for custom.

And maybe that also goes to answer the other question, of why it’s hard for anything to become an institution when somewhere else is always, always coming down the tracks. Back when I was on Tinder (what a fun three months that was) I deplored the way it effectively made you channel hop human beings, with their own lives and aspirations and back stories. Whatever. Next! But the way the food media works does the same thing with a lot of restaurants: one minute you’re the hottest ticket in town, the next you’re old hat.

So I had a lovely meal at Brutto and it taught me a lot about what restaurants do at their best and their worst. I have rarely felt, in a restaurant in the U.K., more like I was part of something brilliant and bigger than me. But ultimately one of the many things that united us that night was being together in the darkness. If that’s not a metaphor for something I don’t know what is. Maybe I’m just too old for all that.

Brutto felt like a neighbourhood restaurant in search of a neighbourhood. And speaking of neighbourhoods, if somewhere like Brutto opened in Reading you can bet I would be there on its opening night, and often after that. The fact that Reading can’t attract and maintain restaurants like this really puts the lie to all the old tut spouted by the likes of Hicks Baker that the town centre isn’t dying on its arse.

But while Reading still doesn’t have places like this, it still has that one thing Reading-haters always extol the virtues of: a train station you can use to get anywhere else. You could do a lot worse than make a reservation, hop on a train and find yourself here, in a place that isn’t quite Italy, isn’t quite London, but most definitely isn’t Reading. I know that’s not exactly hype, but it’s the best I can do.

Brutto – 8.4

35-37 Greenhill Rents, London, EC1M 6BN

020 45370928