On the Wednesday afternoon, my second full day in hospital after the accident, I put some pictures up on Facebook. Nothing special, just a picture from my bed of Dorrell Ward, my left foot poking out, and a shaky, badly photographed picture of my lunch. Well, I never thought this would be my next forthcoming restaurant review my caption read. I know the English is clumsy but in my defence I was dictating it, because typing was too challenging at that point. Besides, I’d probably just had some morphine.

The comments were immediate, plentiful and properly lovely. A couple of the funny ones stuck with me. Chronicle hitman? said one: I replied that it was more likely to be a whack job by the owners of Vino Vita. Another said that is extreme lengths you’ve gone to to obtain a review. I had the comeback in my mind – no stone left unturned, I thought I would say – but looking at my Facebook page, it seems I never posted it. Perhaps the morphine had kicked in by then: I did spend quite a lot of the time asleep, at the rare times when sleep came easily, because that way everything hurt less.

But the thing is, on some level it is a gap that I’ve never reviewed the Royal Berkshire Hospital. Because you could make an argument that it is Reading’s largest restaurant: the trust employs 7500 people, admittedly across more sites than just the RBH, and has over 800 beds. Put that way, it’s hard to imagine that even Reading’s busiest conventional restaurant feeds more people in a week.

So I suppose, in a funny kind of way, this review is sort of overdue. During my four night stay in a place that doubles as Reading’s busiest restaurant, I begin to get an idea of what an unusual beast it is.

* * * * *

I wasn’t meant to wind up an inpatient in the Royal Berks. A whole chain of things had to go wrong for me to be in the place I was and make the decision I did.

First of all, I shouldn’t have been commuting home that Monday afternoon. The previous week I’ve been off with the cold that everyone has had, the cold that wiped us all out. And I only went into the office to catch up with my boss, only to find when I got there that he’d had to take the day off at short notice. If I’d known I would have worked from home, and never made the fateful journey that led to me coming a cropper.

And my boss’s boss, seeing that I was less than 100%, told me to go home early. That played a part too. So I found myself getting off a train somewhere between four-thirty and five o’clock, cutting through Harris Arcade on my way to pick something up from the supermarket. If I’d been later, the arcade would have been closed and I wouldn’t have used it as a short cut. But all those things happened, one after another, and so a little before five I got to the Friar Street end of the arcade to find the shutter in front of the exit halfway down.

In my mind, I thought two things that weren’t necessarily true. I thought that if I headed back to the other end of the arcade, I might find that shutter down too, and then by the time I returned to where I was I’d be shut in the arcade. I also looked at the shutter in front of me and thought to myself I can squeeze under that. And in that respect, I was sort of right: I did manage to shimmy under the shutter.

The problem was that retaining my footing on the other side was completely beyond me.

I went unceremoniously flying, face first into a parked car. My glasses were smashed to pieces, my face bleeding and grazed. But that wasn’t the first thing I noticed. The first thing I noticed was that my arm, in unbelievable pain, no longer felt like mine. I have had to tell this story more times than I can tell you: to friends, to family, to acquaintances, but also to every single NHS staff member who has spoken to me in any capacity since the accident. The first thing they ask you is to confirm your name and your date of birth. But the second thing they say, without fail, is so how did it happen?

I always start with it’s really embarrassing, followed by do you know the Harris Arcade in town? My shame is then compounded by the fact that invariably, whoever I’m talking to knows exactly where I’m talking about: I can’t even make it sound less ridiculous an accident than it was. “I’ve never heard that one before” said the very nice man that took my first x-ray after I was discharged from hospital. Many of the reactions have been variations on that theme.

My wife has heard me tell the tale many times, and has given me tips on how to make it more entertaining which I refuse to follow. Stories in her family are currency, and sitting with them watching them trade anecdotes is one of my favourite things to do, an opportunity to relax and enjoy the show. Zoë tells me that to get a big laugh I should pretend that the shutter was literally rolling down as I reached it and that I chose in an instant to slide underneath it.

But that makes me sound intrepid, or brave, or both. In reality, I’m just a dumb middle-aged man who made a bad decision and went down like an overweight sack of potatoes. The closest I’ve come to taking her advice is this: whenever I tell someone what happened I say I tried to get under the shutter like a shit Indiana Jones. Even that, I’m painfully aware, makes me sound cooler than I really am.

* * * * *

After the accident, in shock and in pain, unable to see, I am peeled off the pavement by Elliott and Alex.

Everyone likes to think that they would stop in circumstances like these, but I think we all know that most people don’t. Elliott and Alex do. They are second year students at the university, who just happen to be in town that afternoon. They ask if I’m okay, and it soon becomes apparent that I’m not. They help me to a bench outside M&S, near the statue of Queen Victoria. They call 999 and put me on the line. The call handler suggests that I should go to the minor injuries unit in Henley. Elliott and Alex are having none of that. I call my wife, still at work, and she picks up because she knows that I never call her when she’s at work.

“Is everything okay?” she asks me. No, I reply. My arm doesn’t work, I say.

Elliott and Alex call me an Uber to get me to the RBH. Getting into it is agony, but they keep talking to me, keep me in the room, keep me distracted. They call their friends and tell them they’re running late, and they ride with me to the hospital and wait with me until my wife arrives, having rushed back from work. These people don’t know me, don’t know anything about me, but they give up two hours of their evening to stay with a stranger, one who’s in excruciating pain and blind as a bat. They only go when they know that Zoë has got home, has picked up some stuff and is in a taxi on her way to me.

We swap phone numbers, and Elliott texts me several times over the weeks ahead. I am yet to persuade him to let me pay for the Uber, but I intend to keep trying. It is the first and probably the biggest kindness I experience, but by no means the last.

After they are gone, I squint at my phone held in my one good hand and wait for Zoë. From down the corridor I hear her at reception. “I’m looking for my husband” she says, and when asked to describe me, she says “he’s big and grey”. I make a mental note never to let her forget this, but I’m just so happy she’s there.

* * * * *

My first experience of the food on the ward, the day after I am admitted, is not the best. Despite the fact that I’m pretty much unable to move, arm in a cast, dosed up with codeine and morphine like clockwork, it hasn’t registered with me that eating with one hand is going to be extremely difficult. I order cornflakes for breakfast, and then realise that sitting up in my bed to eat them is something of which I’m simply not capable. I write that off, because oddly my appetite isn’t what it usually is, and decide I can save myself for lunch.

Lunch is a vegetable risotto, glistening strangely under artificial lights that give it almost an oversaturated look, like a Martin Parr photograph. I push a couple of forkfuls into my mouth and decide these are calories I can do without. Besides, I decide that it looks more like something deposited on a pavement after closing time than the sort of thing I’m used to in pubs and restaurants. At this point, I guess I’m thinking of the Royal Berks as like an all inclusive holiday: you can always sneak in food from elsewhere.

Zoë comes to visit me every day, and between us we soon learn the ecosystem of alternatives in the hospital. The top of the tree is the M&S – “that little Marks & Spencer is a godsend”, Zoë says to me, remembering all the vegetable samosas I smuggled in for her when she spent the best part of a week on the Covid ward. I have a bag of crispy chocolate clouds on my bedside table pretty much most of the time, the challenge being to eat them before the sweltering heat makes them unviable.

And then there’s the hierarchy of coffee. Back when I lived near the hospital I used to walk to AMT for their mochas, and on hot days I’d buy a Froffee, a coffee and ice cream milkshake, and drink it in Eldon Square Gardens, soaking up the sun. I was between jobs back then, and it broke up the afternoons. But AMT’s best days are behind it, and the mocha Zoë brings me one morning is genuinely undrinkable.

Better, to my surprise, is Pumpkin: one afternoon my dear friend Jerry comes to visit me and fetches me a mocha from Pumpkin which is a hundred times better than AMT’s. He also brings me a copy of Viz and the latest Private Eye, which is the kind of thoughtful thing great friends do. I read them at night, by the light of my bedside lamp, after half nine when visiting hours are over and my knackered wife has gone home to get some rest. She keeps me company for 12 hours, every single day, and she never complains.

We aren’t used to spending nights apart, and of all of the things about this that might be one of the most upsetting. The lights are never completely off in the ward, because they’re always coming round to top up your drugs or check your blood pressure. But with my fan whirring, and the other noise abating, the Yves Klein blue curtains drawn around my bed, we send each other good night messages and pictures, and I try to quieten my mind by reading the magazines that Jerry has brought me.

When it comes to coffee the god tier is Jamaica Blue. I reviewed them, over seven years ago, but somehow I’d forgotten about their existence, or how good they were. On the morning of my discharge from hospital Zoë brings me one of their mochas, and for the first time in almost a week I am reminded of how wonderful a thing great coffee can be. It’s a small, tenuous link to my pre-accident life of little luxuries, of V60s at home or my latte at C.U.P, always at 8am, before hopping on the train to the office.

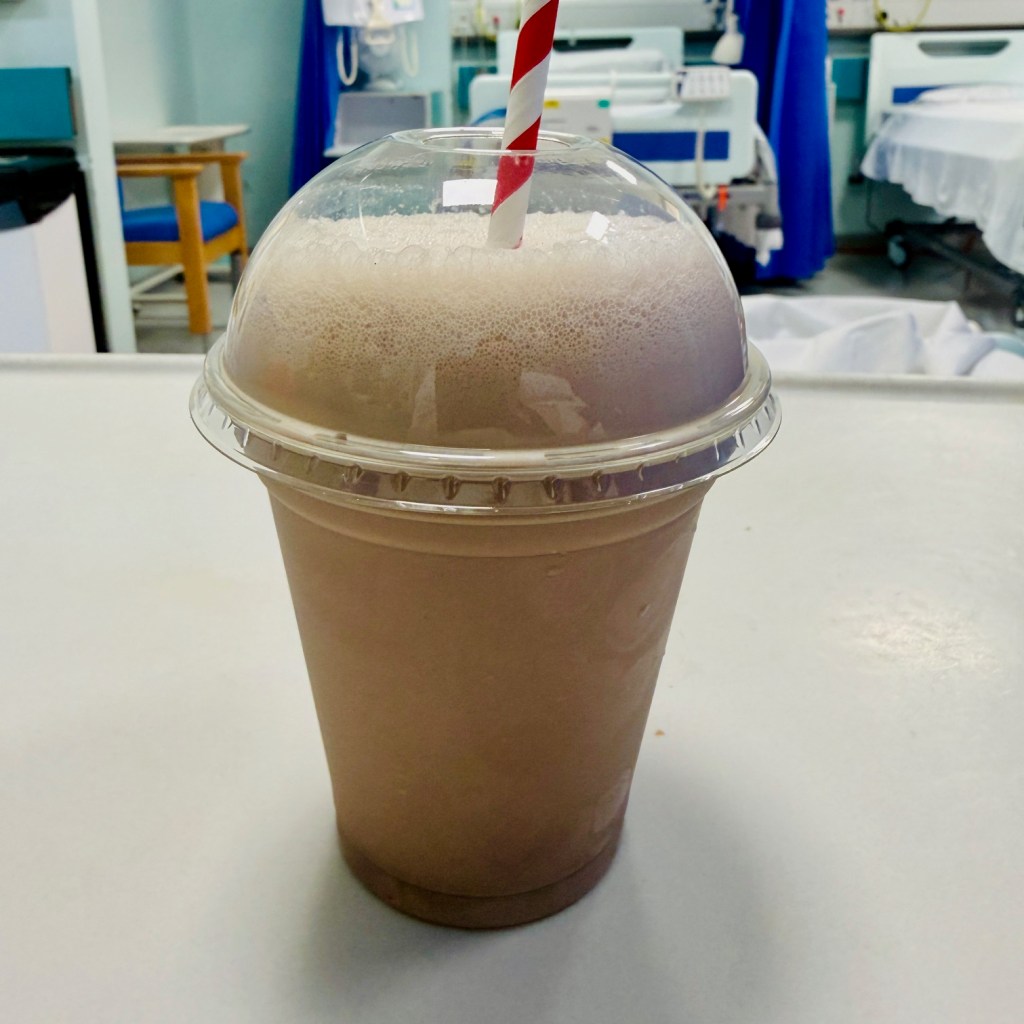

Even better than that, if such a thing is possible, is the milkshake Zoë brought me the previous afternoon from Jamaica Blue, an indulgence so lovely I could almost weep. Thick, cold, chocolatey, more fun than you would ever reasonably expect to have in a hospital. It tastes, to paraphrase Philip Larkin in another context, like an enormous yes.

* * * * *

If I didn’t rely on goodies from the M&S or from the hospital’s cafés as much as I could have done, there was a reason for that. The reason was that the food from the Royal Berks proved to be quite the surprise package.

The menus come round every morning, printed each day, a series of boxes and options to tick for the following day’s breakfast, lunch and dinner. The weeks are numbered, and the font at the top of the menu calls them Lunch and Supper, in Mistral, a typeface you know even if you don’t realise you do. It’s the one from the logo of Australian soap Neighbours, designed in the ‘50s, a beautiful cursive script that is simultaneously retro and timeless. I’ve always loved Mistral, and somehow it brings a tiny chink of sunlight into a room shrouded with blinds.

After that disappointing risotto, somehow I never have another entirely bad meal during my time in hospital. For lunch on my second full day, I have a beef curry with rice and chunks of potato and while I’m eating it, I realise that it’s actually quite good. Not just the absence of bad, although I would’ve settled for that, but decent.

The meat isn’t soft, tender, falling apart as it would be in a Clay’s curry, and the spicing isn’t complex, or even front and centre, but it’s not bouncy, fatty or gristly. The waxy cubes of potato add something, and I find that even with a broken arm, even with a hot uncomfortable cast on me, even with the fan humming and the painkillers wearing off, this is a good meal.

And then, afterwards, an even happier surprise. An apple crumble where the base is sweet, stewed apple but more importantly, the ratio of crumble to fruit is beyond reproach. And by that I mean that it’s easily two thirds crumble, a huge and joyous permacrust of biscuit so thick that I’m fearful, with only one hand, of whether I’ll be able to force my spoon through it. I manage it somehow, and the rewards are considerable.

I include a picture of my lunch with a picture of my ward as I send that first Facebook post mentioning what’s happened to me and where I have found myself. The responses flood in wishing me well, but they also do something interesting that I didn’t expect: a lot of them talk about the food. Because, and I had no idea of this, the hospital makes all of its food from scratch, on the premises, and they serve it in the restaurant as well as serving it to the patients. They could so easily use the likes of Sodexo: how wonderful it is that they choose not to.

One commenter tells me that she used to be the patient services manager for the catering department. The hard work that goes into all of those recipes is outstanding she tells me, and I can well believe it. She also sends me a lovely message with a few tips about what you can and can’t do around the menu, catering life hacks; I thank her for them but decide not to do any of them, because I don’t want to be a diva. The staff start work at 6am every day, she tells me, and work for 14 hours to ensure feeding everybody in the hospital: Reading’s largest restaurant indeed.

So many people comment along those lines, about the food, about the staff, about what a wonderful place the Royal Berks is for people when they need care the most. One of comments says how lovely the hospital’s goulash and spicy lamb are, another recommends the “cultural and religious menu”, a tip that is echoed by Zoë from her time on the Covid ward. The menu just calls it a “ethnic meal”, but I order it multiple times and am never disappointed.

Somebody else tells me that she’s been a patient at the RBH on and off for 18 months. The food is one of the highlights she tells me. It sounds silly, but all these intersecting stories, this universality of experience makes me feel less alone, and less scared. It also reinforces that even if I have very limited experience of this hospital – this is the first time I’ve ever spent the night in a hospital since I was born – the RBH is at the centre of Reading life, and it touches everybody.

It was there when my wife was taken away from our house in an ambulance late at night for a prolonged stay on the Covid ward, in the depths of winter 2021. Both of my sisters-in-law were born there, so were both of my beautiful nieces. It’s the RBH that treated my father-in-law when he had cancer, and again when he had a heart attack. And that’s just my family – but from the pile of comments I got a clear impression that it was central to countless more families than mine.

I never quite get over not hating the food. The following day I have a beef stroganoff which again, is just downright comforting and nice. The little mini packets of biscuits are by Crawfords, and are really enjoyable with a cup of hospital tea; I allow myself two sugars while I’m in hospital, it seems only right. The ice cream is lovely too, despite not resembling any ice cream I would buy for myself on the outside. You almost need to eat it first, because by the time you finished your stroganoff or your keema curry – accompanied by a little pot of dal or vegetable curry – it is a texture almost like foam.

* * * * *

One of the comments on my Facebook page says NHS toast is up there. And there is truth in that, too: every morning my breakfast form requests white toast with butter and Marmite, and there is real comfort in eating that around 8am, when the ward starts to stutter to life and the shifts change over, when you give up hope of getting any more shut eye until the afternoon.

With only one arm, I have to ask the nurses to butter my toast and put Marmite on it. Every morning I luck out, either getting a nurse who loves Marmite or, equally likely, one who has never tried the stuff. The tub they bring is generous, and it is generously slathered on. I eat it in silent gratitude, and then I attack my sweet white tea, a drink I haven’t had for the best part of a decade.

* * * * *

Everyone says this, but it’s true: the staff at the RBH are uniformly fantastic. From the people who butter my toast to the ones who help me adjust my bed, from John, the helpful nurse on my final morning who walks me to the loo and protects my dignity to the two T-level students who are spending the week helping out on my ward, who take my blood pressure across the four days with gradually increasing proficiency, everybody is amazing. From the porters who wheel me across the hospital in my bed for a CT scan to the staff who somehow managed to roll and transfer me from my bed into the scanner – while again protecting what little dignity I have – it’s impossible to express admiration or gratitude adequately for them.

And everybody knows everybody, the porters greet each other as they pass in corridors, the way bus drivers do. The staff have an incredible spirit and I can only imagine the strain that is put under, every single day. At the time I’m simply emotional and grateful and full of feelings in a way that suggests that, the rest of the time, they’re probably buried further below the surface than they should be. I’ve spent more of the last five weeks crying then I have the five years before that.

It’s only later on, when I get home, that I feel angry that things should be so difficult for the people that work there. During the pandemic, I always neglected to stand outside my house and bash a saucepan with a wooden spoon, to clap for carers. I found it performative, I felt like it had been suggested by a government that did not care for that sector one iota, and did nothing to protect it from the virus. I told people that I did my bit for the NHS by voting Labour. But now I realise that’s also performative, only in a different way, and just as bad. I resolve to donate to the Royal Berks’ charity when I get out, to support their extraordinary work.

* * * * *

Around Thursday lunchtime Melinda, one of the nurses looking after us that day, stops by my bed and asks me if I write this blog. She follows me on Facebook, and has seen the picture of my foot in the ward. I’d know that ward anywhere, she tells me. I own up, and we have a little chat about that, a touching little moment of connection which comes out of nowhere. I tell her that if she wants to feel really proud of where she works, she should go to my Facebook page and read the comments.

I mention this anecdote on Facebook a few days later when I’m convalescing at home, and someone else pops up in the comments. Me and that same nurse had this conversation in the staff kitchen and she showed me your post and that’s how I was introduced to your page she says. It’s nice to feel social media bringing people together, because there are so many reminders day in, day out of it doing precisely the opposite.

Later on Thursday afternoon, a doctor comes by to chat to me about my discharge the following day. The junior doctors are on strike tomorrow, and everything is being prepped in advance so I can check out without any undue delays. She asks how my time in hospital has been and as I’ve done here, as I’ve done with everybody who has asked since I got home, I pretty much gush about the amazing work that happens in the Royal Berks.

“I really hope you didn’t mind the food” she tells me. “We get quite a lot of complaints about that.”

“Actually I liked it” I reply. I think about it for a second, decide to blow my cover. “I write a restaurant blog in my spare time and the food here, and the way it is managed here has really impressed me.”

“You’re not Edible Reading, are you? I’m pretty sure I follow you.”

This might be the closest to fame that I’m ever going to get, but really I’m not at the epicentre of this story. The hospital is. Mine is just one of thousands of stories about this institution, one voice straining to be heard in a gigantic choir singing its praises. That is absolutely as it should be.

When I finally leave on the Saturday, gingerly shambling out into the daylight with Zoë to the car park where my father-in-law is waiting, my relationship with the RBH is far from over. There will be x-rays, they will fit a brace, they will do more x-rays, they will determine that the brace isn’t enough, and they will decide to operate. The fracture clinic is right next to Jamaica Blue: I grab a coffee to fortify myself before every appointment.

There will be a day when I sit there in the Day Surgery ward for seven hours, starving and anxious, while I watch everyone else go off for their surgery, come back and go home. There will be a conversation with the anaesthetists, where I only remember the beginning and then come round, groggy and in recovery, hours later. There will be that first phone call with Zoë afterwards, when I let her know that I’m still alive and enjoy the miracle of hearing her voice again.

And there will be one more night in the hospital, back on Dorrell Ward. It might be a happy accident, or it might be deliberate, but they take me to the same ward and park my bed in the same bay. One of the nurses on duty was on duty when I first stayed in hospital. You again, she smiles. The next morning, the wife of the chap in the bed next to me comes over to talk to me and Zoë. “I’m so glad they put him in Dorrell” she tells us. “It’s the best ward in the hospital.”

I don’t know. Perhaps everybody says that. But it was hard not to feel like it was the best ward in the hospital, or that I was the best hospital in the country. Because they and their extraordinary staff took what would have been the most frightening, lonely and anxious week of my life and made it somehow a week of peace, care, healing and – let’s not forget – Marmite.

So that’s my review of the Royal Berkshire Hospital. A place of peace, care, healing and Marmite. A place that is Reading’s biggest restaurant by accident, not design, and one that happens to be a restaurant many times better than it needs to be. It’s also the most paradoxical place I will ever review. Because obviously I sincerely hope I never eat there again, and I wouldn’t wish a meal there on my worst enemy. But if you do find yourself there, and many people do, every single year, I cannot say enough good things about it. The food’s not bad, either.

The Royal Berkshire Hospital

London Rd, Reading RG1 5AN

0118 3225111

https://www.royalberkshire.nhs.uk

Since January 2025, Edible Reading is partly supported by subscribers – click here if you want to read more about that, or click below to subscribe. By doing so you enable me to carry on doing what I do, and you also get access to subscriber only content. Whether you’re a subscriber or not, thanks for reading.